DiDi Global 滴滴

Light at the end of the tunnel

Thesis

The holy grail of value investing is buying high-quality companies at bargain prices. Such opportunities occasionally arise during crises unrelated to the companies’ fundamentals. Such crises not only send companies’ stock prices to attractive levels, but also offer valuable tests to their competitive strength.

I believe DiDi presents such a rare opportunity. The great thing about this idea is that as long as I’m directionally correct on the key business drivers, chance of permanent loss is remote and DiDi shares are easily worth multiples of the current stock price. Below is a simple back-of-the-envelope calculation demonstrating the large margin of safety.

DiDi’s share price has ranged between $3/share – $5/share since 2023. At an average cost of $4/share, this is around ¥134B market cap. Backing out around ¥30B in net cash,1 the enterprise value is only ~11x the EBITDA of DiDi’s China segment. Compared to Lyft’s 15x multiple, this is a punitive valuation — probably justifiably only if DiDi were to lose significant market share in China going forward.

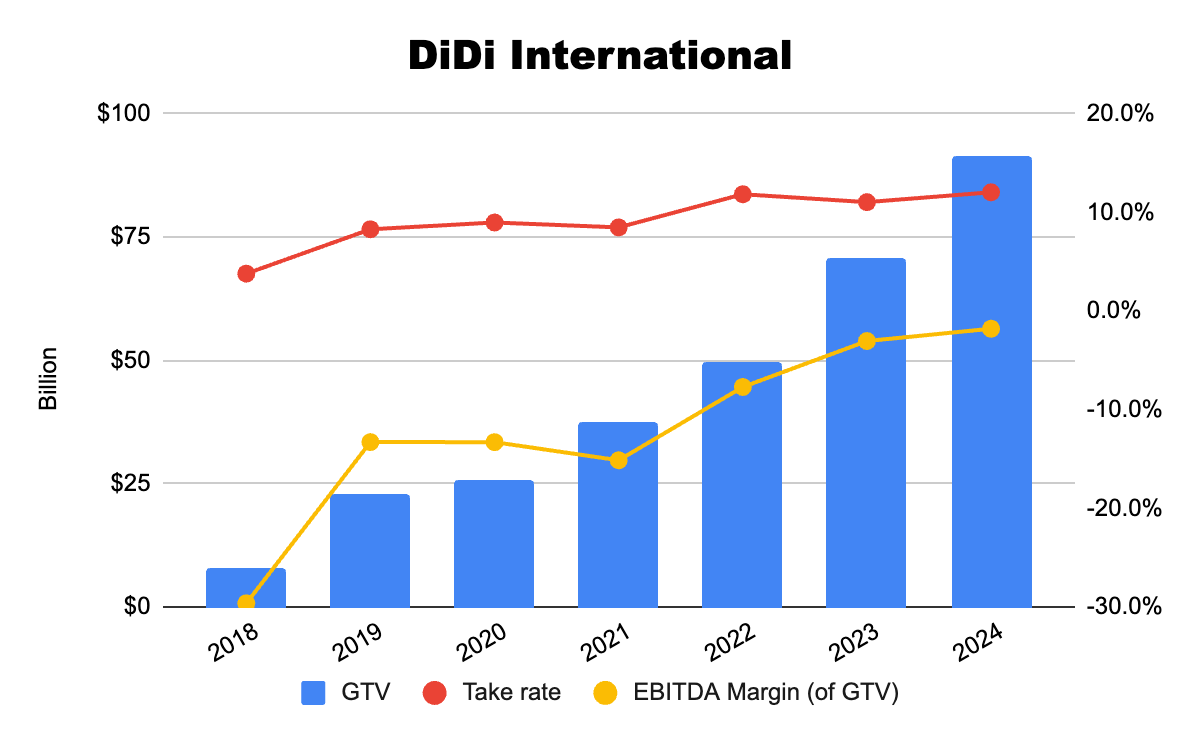

And what does the market give us for free? A fast-growing international business with ¥90B GTV, 30% yoy growth and steadily improving margins; a 3% stake in Grab worth around ¥5B (likely undervalued at current market price); and a bike-sharing business with one-third of China’s market share.

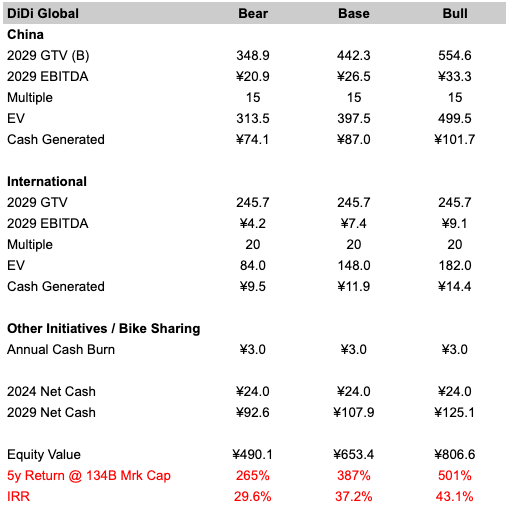

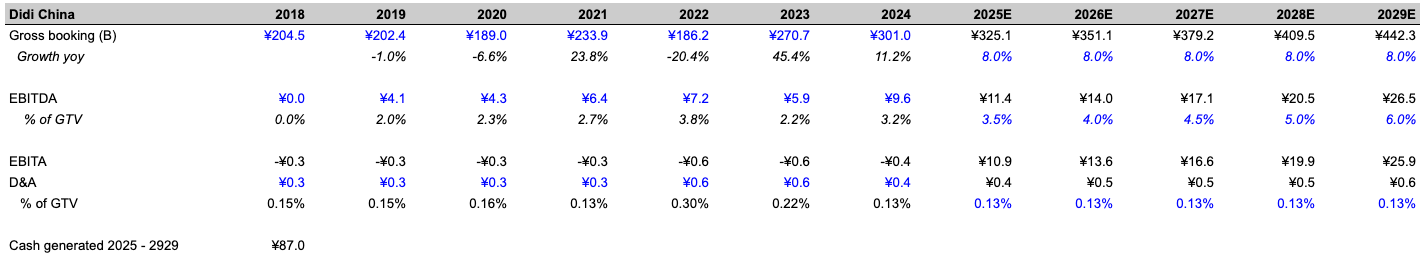

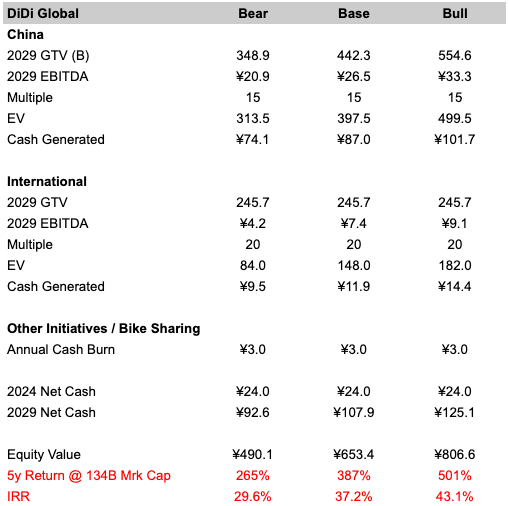

My valuation model estimates DiDi’s worth at ¥500B to ¥800B, based on segment-level cash flow projections from 2025 to 2029. This implies a total return of 260% – 500% over the next five years, or 29% – 43% compounded annual return, as summarized in the table below.2

Key Business Drivers

At a high level, I have greater conviction in margin expansion than top-line growth for DiDi’s China segment—and the opposite for its international business. This is reflected in my model, which incorporates a range of assumptions for the lower-conviction drivers. Each of these key assumptions is discussed in detail later.

In China, DiDi’s massive scale flywheel creates strong competitive advantages and a high barrier to entry for smaller players. I think investors are over-pessimistic about China’s competitive environment. A cut throat price war is unlikely over the next 5 years, given a more rational capital market. Partially this is attributed to a tougher stance taken by the government on excessive competition, which undermines its strategic goal of boosting domestic demand as a key driver of China’s future economic growth.

DiDi’s competitive strength is well-tested by the cyber security investigation during which new user registration was suspended for one and half years. I believe the current 7/3 ~ 8/2 market share split between DiDi and aggregated small players is a stable equilibrium state, serving a solid foundation for DiDi to expand margin and capture future industrial growth.Given its dominant market share, DiDi’s future top line growth in China will be driven by industrial growth. Given that ride-hailing trip volume in China remains 3 to 4 times lower than in the U.S., I see substantial potential for further penetration in the Chinese market. With fare prices anchored to heavily regulated taxi rates and ride frequency improving on a long time scale, I identify penetration rate as the primary driver of DiDi’s GTV growth over next 5 years. I model GTV CAGR of 3% - 13%, translating to ¥350B - ¥550B GTV in 2029.

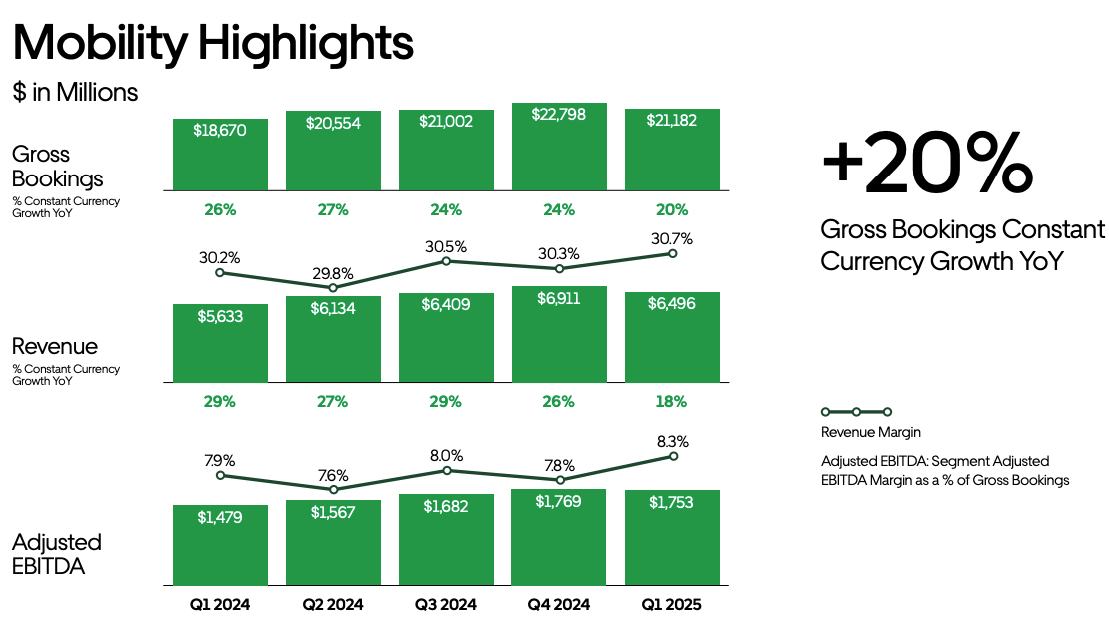

Aiming at Uber’s 8% EBITDA margin in 2024, I project that of DiDi China expands to 6% by 2029, factoring in the lower-margin taxi-hailing contribution. With DiDi’s dominant position and expected rational competitive environment, I think this is achievable, say with 1% increase in take rate, 1% reduction in consumer incentives and 1% from operating leverage. Take rate expansion is supported by both the oversupply of drivers due to soft economy and the declining per-trip cost driven by rising EV ownership in China. Margin expansion due to operating leverage might be conservative as I suspect DiDi’s operation in China enjoys a greater local economy of scale than Uber’s global business.

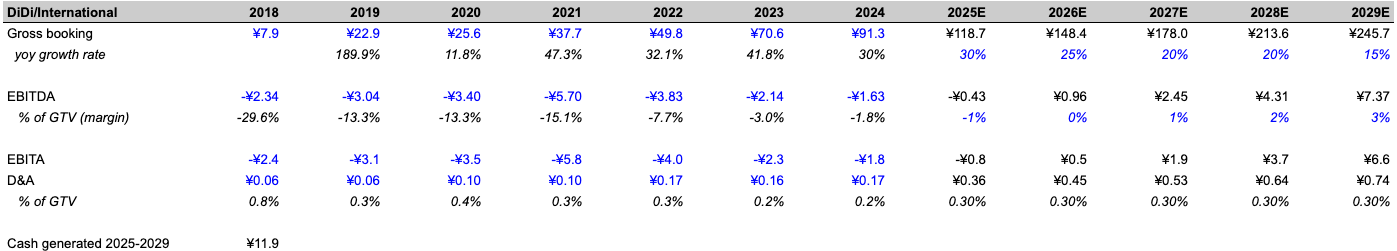

DiDi’s international business, mainly in Latin America, has scaled rapidly and built a strong multi-vertical ecosystem across ride-hailing, food delivery, and financial services. With fewer entrenched competitors and strong local execution, this segment is well-positioned for continued expansion. I expect its annual growth rate to remain strong, gradually slowing from 30% to 15% over the next five years.

I believe the Latin American market will likely play out like the North America, where Uber and Lyft moved past the prisoner’s dilemma to achieve profitability. DiDi and Uber are expected to do the same—why hurt each other when Uber owns 10% of DiDi? I think Grab is a better near-term reference here, given its recent profitability and a similar market structure in ASEAN. Based on this, I project DiDi’s international segment will reach a 2%–4% EBITDA margin by 2029.

DiDi has scaled back its non-core, cash-burning ventures. Following the sale of its smart auto subsidiary to XPeng in 2023, bike-sharing is now the only alive one in the Other Initiatives segment. There are signs the three major players in this space are nearing profitability, supported by recent price hikes and improving user engagement. To be conservative, I assume DiDi will continue to post a modest EBITDA loss of ¥1B annually for this segment. Combined with ¥2B in capex for bike purchases, I estimate total annual cash burn at ¥3B.

Is there a risk that DiDi could return to wasteful capital allocation in the future? It’s possible, but I think it’s unlikely in the near term—at least not until it relists in Hong Kong and experiences a period of strong stock performance.

Why does this opportunity exist?

DiDi is a Chinese company trading OTC. Most institutional investors stay away from OTC stocks. Not only it’s a Chinese company—DiDi was publicly and severely punished by the CPC. For investors already wary of China exposure, DiDi likely ranks as the poster child for China risk.

DiDi is underfollowed. Since its 'voluntary' delisting from the U.S. in 2021, there has been no analyst coverage for three years. The company also deliberately stayed out of the spotlight following the cybersecurity investigation.

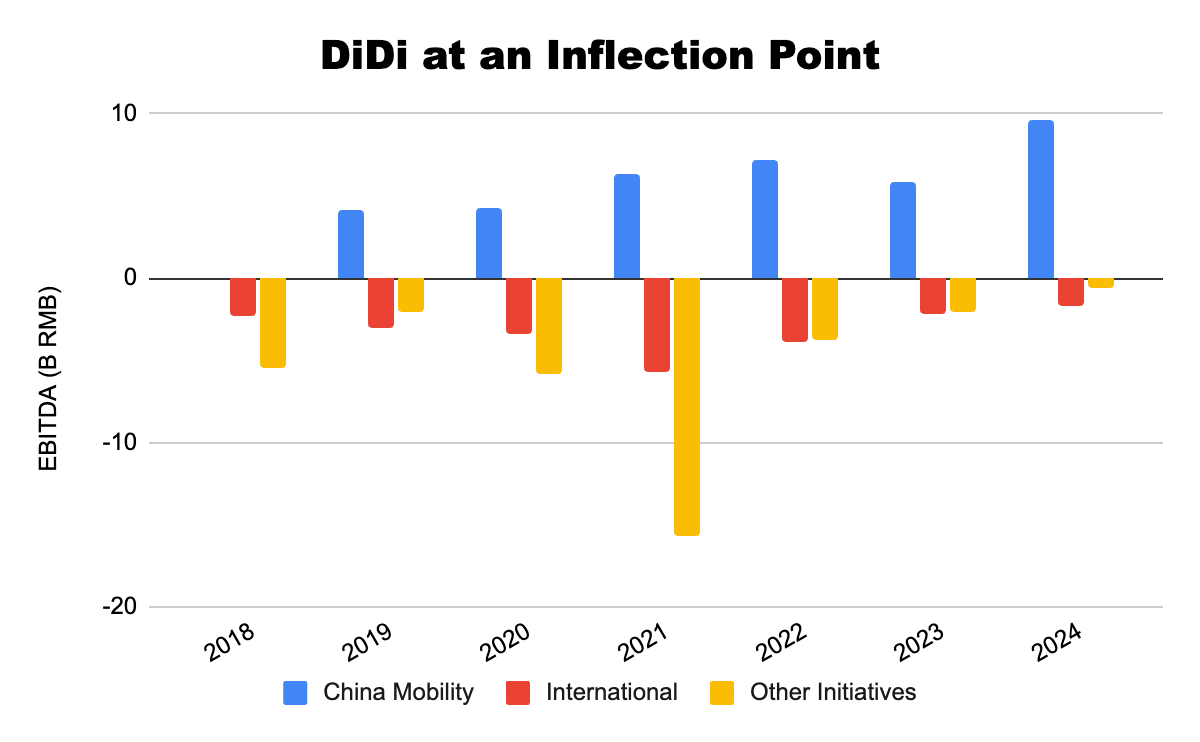

Divergent cash flow streams easily misunderstood by market. On a gross basis, DiDi is trading at 123x PE. However, on a STOP basis, we find a growing China segment, an international business growing at 30% with consistently improving margin profile, and significant cutback on cash-burning ventures. I believe DiDi is at an inflection point where its profitability is about to become visible to the market.

Catalysts

Relist in Hong Kong stock market

Several signs suggest this process may already be underway. In May 2024, DiDi President Liu Qing — who is believed to be heavily involved in DiDi’s IPO — stepped down as president and was 'promoted' to permanent partner. In October 2024, China Renaissance, one of the underwriters of DiDi’s IPO and the firm that led the DiDi-Kuaidi merger, initiated its first coverage on DiDi. In May 2025, the CSRC Chairman publicly stated that they would create conditions to support the return of high-quality U.S.-listed Chinese companies to the domestic and HK stock markets.Uber’s continue strong stock performance

Before 2022, Uber was plagued by negative headlines—clashes with local authorities, conflicts with taxi unions, scandals around CEO, and widespread skepticism about the viability of its business model. Since then, however, Uber’s stock has surged nearly fivefold, and the company generated $10B in earnings last year.

SoftBank clearly exited Uber too early—likely not by choice. It has invested around $12B in Didi and holds a 20% stake, meaning Didi would need a $60B market cap—close to my bear case valuation—just for SoftBank to break even.

In many ways, DiDi’s story mirrors Uber’s: similar regulatory headwinds, the same tendency to burn cash on non-core ventures (not surprising, given Masa’s involvement in both). This resemblance, combined with Uber’s recent success, could help shift investor sentiment and lead to a market rerating for DiDi.Stock buyback

DiDi spent approximately $850 M on share buybacks in 2024. In March, management announced an another 24-month $2 billion repurchase plan. If fully executed, this would represent about 10% of DiDi’s market capitalization.

China Mobility I: Competitive Strength

In this section, I’ll explain why I believe DiDi’s competitive moat in China is stronger than perceived, positioning the company to expand its EBITDA margin by 300 basis points. This would effectively double its EBITDA, even assuming a flat top line.

Broken Bear Thesis

Before diving into DiDi, it’s worth briefly mentioning the once popular bear thesis on ride-sharing performs, as it is such a classic example of what Buffett famously said “the rearview mirror is always clearer than the windshield”.

Back in 2017, the year Uber founder and CEO Travis Kalanick resigned amid a series of scandals, Len Sherman published a Forbes article arguing that ride-hailing platforms were inherently unprofitable.3 Over the following years, Sherman and others doubled down on the idea.4 In 2022, a short thesis on Uber appeared on VIC5 —arguably one of the worst-written post in the club—but it reflected the skepticism among investors at the time. Ironically, Uber’s stock price went up 5x since then.

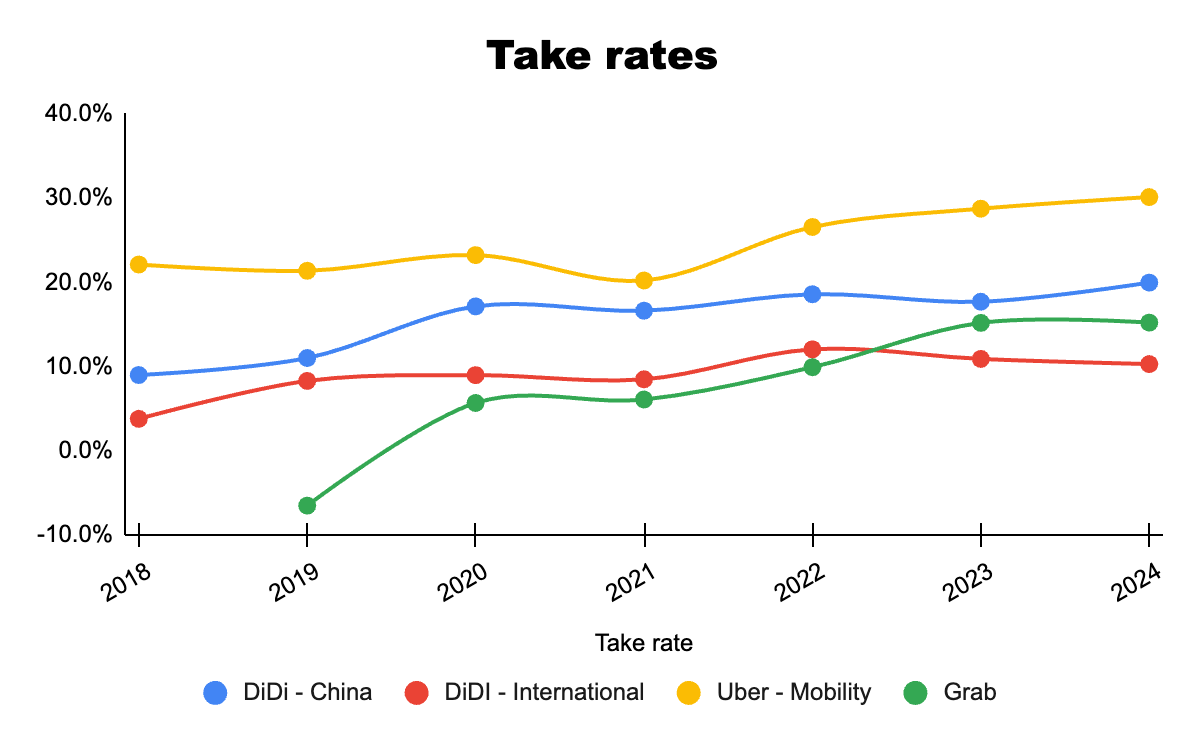

The core of the bear case was that ride-sharing platforms lacked strong network effects, resulting in low switching costs and an inability to raise take rates without losing drivers or riders. But network effects or not, this thesis has been clearly disproven by the consistent rise in take rates—and EBITDA margins—across all major ride-hailing players.6

I believe the critics made a fundamental error: they misattributed the price wars—classic examples of the prisoner’s dilemma that have played out across many industries in history—and the wasteful capital allocation, a byproduct of a time of excessive liquidity, to inherent flaws in the ride-sharing business model.

Massive Scale Flywheel as Moat

With 70% ~ 80% market share, DiDi facilitates 12.4 billion rides annually and has become the default platform for nearly all drivers in China. This dominant position gives DiDi a fundamentally different—and in my view, easier—challenge than its competitors: instead of acquiring new drivers, its primary task is retaining the ones it already has.

To enhance driver engagement, DiDi has increasingly ties drivers’ income ties to their ratings: 7

“If you skip work one day or don’t start driving on time during the morning or evening rush hours, it will affect your rating on the platform, and the number of ride requests you receive will drop significantly.”

— A DiDi driver interviewed by 36Kr

A key component of a driver’s rating is the fulfillment rate, which reflects how reliably a driver accepts and completes rides—a strong indicator of platform loyalty. Multi-platform drivers often cancel rides when receiving simultaneous orders from competing apps, a behavior DiDi now penalizes heavily.:

“If you cancel an order, the service score deducted from that one cancellation will take 500 completed rides to recover.”

— A DiDi driver interviewed by 36Kr

This system makes it extremely difficult for smaller rivals to poach drivers from DiDi. In practice, only low-rated drivers—often with subpar service quality or non-compliant vehicles—opt for alternative platforms. This creates a virtuous cycle for DiDi: high-quality drivers are retained, user satisfaction improves, and the platform's brand reputation continues to strengthen.

The scale brings DiDi’s two more advantages:

First, the traffic and ride data it has accumulated over the past decade is an invaluable asset. This data powers superior algorithms for dynamic pricing, driver-passenger matching, and arrival time predictions—features that directly affect user experience and are difficult for smaller players to replicate.

Recently, Professor Len Sherman proposed that Uber’s profitability is largely driven by its AI’s ability to apply price discrimination on both riders and drivers, maximizing its margins.8 If that’s true, it only underscores the potential value of DiDi’s large dataset. Higher margins mean more resources to reinvest in product improvements and to fend off competition.

This same data also creates a strong foundation for expanding into future value-added services, and DiDi’s accumulated mobility data gives it a strategic edge that autonomous driving companies cannot easily bypass.

Second, ride-hailing is a highly localized network business, where new entrants typically have to build up one region at a time. DiDi, on the other hand, has already reached critical mass in all major urban areas in China. With national scale and resources, it can wage a prolonged competitive battle if necessary—creating significant barriers to entry for new players.

Prisoner's Dilemma Will be Tamed

History has taught us that the ‘prison dilemma’ eventually will be tamed via various structural changes and tactical response strategies. Competition eventually reaches a collaborative equilibrium.9 In fact, I think the current 7/3 ~8/2 market share split between DiDi and other aggregated smaller players is approaching such equilibrium state for the follow reasons:

The aforementioned reward and punishment mechanism by DiDi effectively creates a structure change that avoid direct competition. Drivers with high quality service and users who would pay a premium for such quality gathers on DiDi while users who is more price sensitive chooses smaller platforms.

Another structural change is a more rational capital market. After years of aggressive expansion and land grabs, internet companies are now slamming on the brakes. In August 2022, Huawei founder Ren Zhengfei published an internal memo warning that the global economy was heading toward recession and declining consumer spending. He stated that the company would shift its focus from scale to profitability and cash flow, making “survival” the top priority. In 2023, Tencent’s investments had dropped to just 37—its lowest point in a decade and less than half the number in 2014.

This retrenchment isn’t limited to Huawei and Tencent. Since 2022, China’s internet giants have been pulling back. Companies like Alibaba, ByteDance, Baidu, and Meituan all halved their external investments compared to the previous year. Earlier this year, ByteDance even shut down its strategic investment division entirely.

Behind this shift is also guidance at the national policy level. Over the past few years, the Chinese government has repeatedly summoned and advised companies across various industries to curb excessive, cutthroat competition. In 2024, Xi for the first time in a Politburo Standing Committee meeting, explicitly called for preventing involution-style competition. Why is the government placing such emphasis on this issue? Because excessive competition runs counter to China’s strategic imperative to boost domestic demand as a key driver of future growth.

In summary, I believe cutthroat price wars in the ride-sharing sector are unlikely in the next 5 years, the current 7/3 ~ 8/2 market share split is an stable equilibrium state.10 This presents an excellent opportunity for DiDi to further strengthen its position and improve profitability.

Is Aggregator Platform a Big Threat?

As some investors are worries about the aggregator platform, emerged together with small new players during the time of DiDi’s investigation, I will briefly comment on this here.

Essentially, a aggregator platform such as Gaode let user compare and choose offers from different ride-hailing platforms. Why did Gaode get a lot of traction around 2022? On one hand, Gaode was looking for monetizing its huge internet traffic from its map service (~800M MAU). On the other hand, small ride-hailing players desperately need user traffic to grow, eroding DiDi’s market share. It’s a perfect math for both sides.

However, I don’t not think it will pose a big threat to DiDi for the following reasons:

The business model itself is flawed which inevitably leads to worse user experience, regulation problems and low service quality. Specifically, aggregators don’t directly manage or vet drivers, control driver incentives, dispatch algorithm and customer services. This means they can’t optimize wait times, pricing or issue resolution process as well as DiDi.

Aggregators taking additional cut means a lower income for drivers given small players cannot afford to increase fare price. This is unattractive for well-trained drivers with better service.

Gaode is not focused on ride-hailing business— it is just one of many attempts to monetize their map service. Ad revenues and O2O are the other two pillars. Further more, with Tsai and Wu stepped up, Alibaba is refocusing on e-commerce and cloud service. The Local Life segment, which Gaode was part of, is not Alibaba’s core business any more. Therefore, I doubt how focus Gaode is and how much it is supported to take more market shares from DiDi.

A Test of DiDi's Moat

It’s important to have some quantitative data supporting my argument.

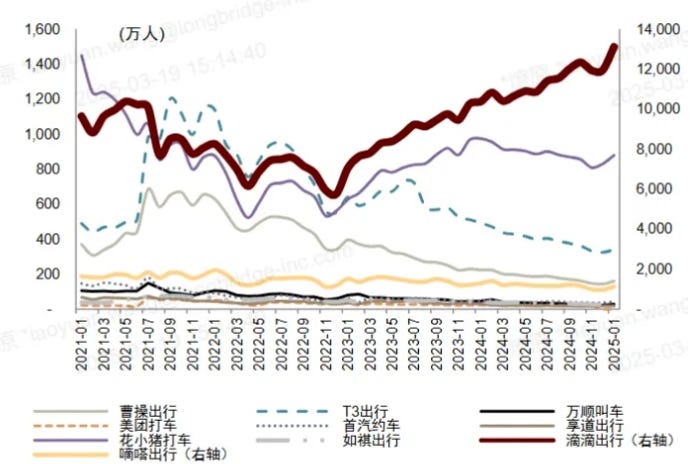

In 2021 the Chinese government launched a cybersecurity investigation on DiDi. During that period, DiDi’s apps were removed from app stores and new user registration was suspended for one and half years. Study of how the market reacted to such external event offers a quantitative test to my argument on DiDi’s competitive strength.

During that period, competitors such as Caocao and T3, backed by major Chinese automotive manufacturer, rapidly expanded into new cities and offered substantial subsidies to attract both drivers and riders. Although the Chinese authorities urged everyone to stop “vicious competition”,11 DiDi’s market share was still declined from 90% to 70% by the end of 2022.

However, since user registration recovered in 2023 and the lifting of lockdown, DiDi’s MAU rapidly rebounded and already surpassed its 2011 level. According to various reports, DiDi market share recovered to around 70% ~ 80%. Recall that during that period, Chinese netizens frequently described DiDi as a “traitor” and “walking dog” of the US. How could there be new users when registration reopened, if DiDi’s product and service has no competitive advantages?

China Mobility II: GTV Growth

Many believe DiDi has limited growth potential in China given its dominant market share. While the hypergrowth phase may be behind us, I think the long-term growth of the ride-hailing industry remains underappreciated. In 2023, the traditional taxi-hailing market was still larger (¥323 billion) than ride-hailing (¥282 billion).12 I believe it’s only a matter of time before ride-hailing fully replaces traditional taxis, suggesting the ride-hailing market could at least double from here.

To study DiDi’s GTV growth potential in detail, I first break GTV into trip volumes and fair price.

Fare Price

There is very limited up room for fare price for two reasons: 1) it is anchored to taxi rate, which is strongly regulated. 2) According to Wind, from 2006 to 2021, per mile rate for taxi in 36 cities of China grown from ¥1.66 to ¥1.98, lower than CPI growth. Therefore, I expect DiDi’s average fare price grow at 1% CAGR and is around ¥26 per ride in 2029.

Trip Volume

According to the Ministry of Transport, total taxi and ride-hailing passenger volume in China reached 35.8 billion in 2024.13 DiDi’s China Mobility segment recorded 12.4 billion transactions that year. Assuming DiDi holds a 70%–80% market share, this implies a roughly 1:1 ratio between ride-hailing and taxi trips. In contrast, China Renaissance estimated this number to be 3:1 ~ 4:1 for the US.

If China were to reach a 3:1 ~ 4:1 ratio, assuming total taxi+ride-hailing trip volume remain constant, it would imply a 50% ~ 60% upside potential for ride-hailing. A 10% CAGR suggests this could be achieved within the next five years.

Trip volume can be further breakdown as follows:

Trip volume = Population base x Penetration rate x Monthly Trips per Consumer

Penetration Rate

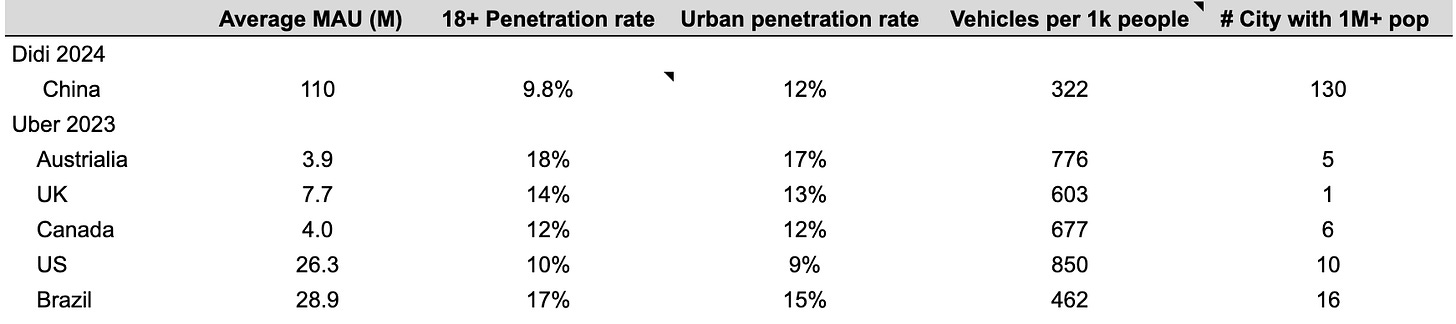

There are more than one way to define penetration rate. Uber defines it as MAU/18+ population, and publishes this number for different countries in their investor presentations. This provides us valuable benchmark for our analysis. One alternative is to use urban population in the denominator. I think the later is probably more accurate as China has a much lower urbanization rate than developed countries.

I compile the following table based on the penetration rates disclosed for Uber’s international markets:14

The numbers for DiDi should be taken with a grain of salt, as it’s difficult to obtain accurate its MAU data, for several reasons. First, DiDi no longer discloses MAU figures. Second, users in China can access DiDi through both the standalone app and the WeChat Mini Program. I used the DiDi app MAU from QuestMobile, which likely underestimates the true number. Third, QuestMobile reports that DiDi’s WeChat Mini Program reached around 300 million MAU in December 2024 — a figure that seems unusually high. This number may be overstated, as it likely includes users of other services within the Mini Program ecosystem, such as bike-sharing and intra-city freight.

On one hand, If we use DiDi APP’s MAU of ~100M, Didi’s penetration rate in China is roughly equal to that of North America, but is quite low comparing to Australia and Brazil.The actually difference should be slightly larger, as we are comparing Didi’s 2024 number with Uber’s 2023 numbers.

On the other hand, China Renaissance pointed out that DiDi’s MAU reached 200 million around 2023. This figure might be more credible, as it was probably sourced directly from management. Based on a 200 million MAU estimate—and adjusting for DiDi’s and Uber’s respective market shares15—China’s ride-hailing penetration rate already surpass that of North America and be roughly on par with Australia and Brazil.

In any case, the table indicates that the global penetration of ride-hailing platforms remains below 20% — a quite low figure if we believe ride-sharing is fundamentally transforming how people travel.

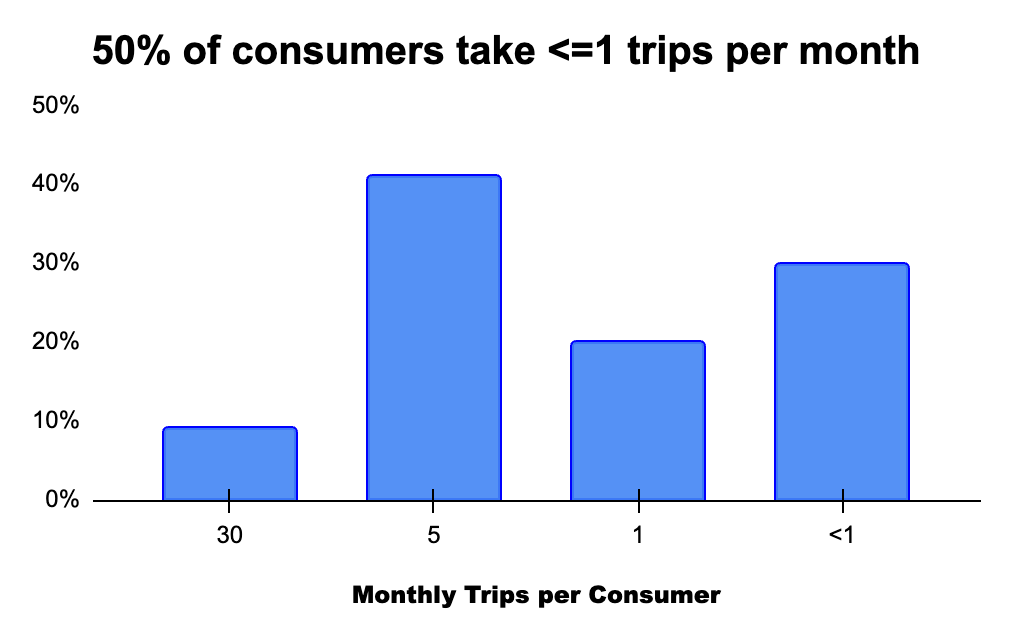

Monthly Trips per Consumer

Regarding the MTPC, defined as total order number /MAU/12, the number is around 5 rides per user per month over the past two years (using 200M MAU according to China Renansance). I didn’t find any more fine-grained data from DiDi, but a survey from iiMedia back in 2021 shows that 50% of ride-sharing users contribute one or less than one ride per month. This distribution actually largely agrees with what Uber published in the investor presentation.

I expect the MTPC to further improve 1) as the rise of new generations with better adoption of share economy, and 2) as DiDi continue exploring more diverse niche use cases. For instance, DiDi launched a version specifically designed for 60+ users in 2021, and offered the option of riding with pets in 2024.

I don’t observe any consistent pattern suggesting MTPC improved much over the past 5 years (could be affected by COVID), suggesting it might be a long-term driver. I assume MTPC increased by 0.5 ~ 1 rides by 2019, contributing around 2% ~ 4% to the GTV CAGR.

2025 - 2029 GTV Growth Projection

In summary, I think the primary driver for DiDi’s GTV growth in the near term will be increased trip volume or penetration rate. Contribution from the fare price and MTPC growth won’t be more than 3% annually. I model penetration or trip volume grow at a CAGR of 0%, 5% and 10% for my bear, base and bull case, respectively. Assuming flat population growth (which seems to be expected if not decreasing) and negligible urbanization rate growth,16 this implies overall GTV CAGR of 3%, 8%, and 13%, translating to ¥349B, ¥442B, and ¥554B by 2029 in each case.

Is my projection of GTV growth rate too opmtisitc? Probably not, given even my bull case is lower than several quick estimations shown below:

GTV growth rate for Didi were 45.4% and 11.2% in 2023 and 2024, respectively. The 2024 slower growth is mostly like distorted by the abnormally strong growth in 2023, due to both the recovery from Covid and lift of government ban. Therefore, low teen might be reasonable for a normalized growth rate over the next few years. In contrast, Didi’s younger international business growing at 30%.

Frost & Sullivan projects China’s ride-hailing GTV will climb at 19.5% CAGR from 2024 to 2028, as the segment expands from 41.4% to 52.2% of total car-based passenger-transportation GTV.17

Lyft does not have delivery business thus serve a very good comparable. It’s GTV grown at 15% on average over the past two years. With only 30% market share in US and Canada, its growth rate should be a good lower bound for DiDi’s China business.

China Mobility III: UE & EBITDA Margin

Margin projection requires a clear understanding of DiDi’s unit economy and its financial model, as they are quite different from those of Uber, which provides the target for our projection.

Unit Economy

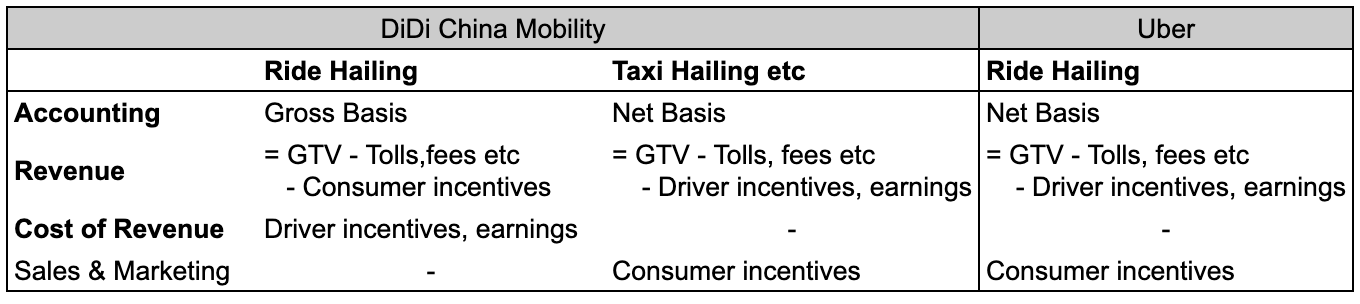

DiDi’s domestic business has two revenue streams which are treated financially different. For Ride Hailing, representing 79% of its GTV, DiDi considers itself as the principal and records the revenue on a Gross Basis. The other smaller contribution is from taxi hailing etc, where DiDi considers itself as an agent, recognizing the revenue on a Net Basis. For Uber, however, there is only one stream, which is the Ride Hailing and is recognized on a Net Basis.

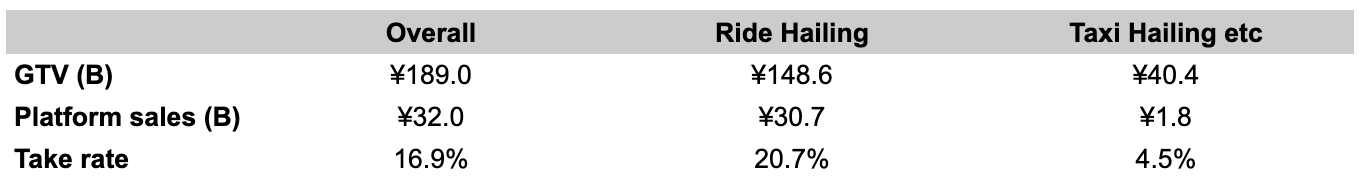

Consequently, the comparable segment of DiDi and Uber, aka Ride Hailing, are treated differently in their financials. This is summarized in the table below:

To calculate the take rate for Uber is simple — just dividing its GTV by revenue. For DiDi, however, we need to divide its total GTV by the Platform Sale18 which is disclosed separately. Another issue is that the take rate calculating this way is a mixture of take rates of DiDi’s two revenue streams.

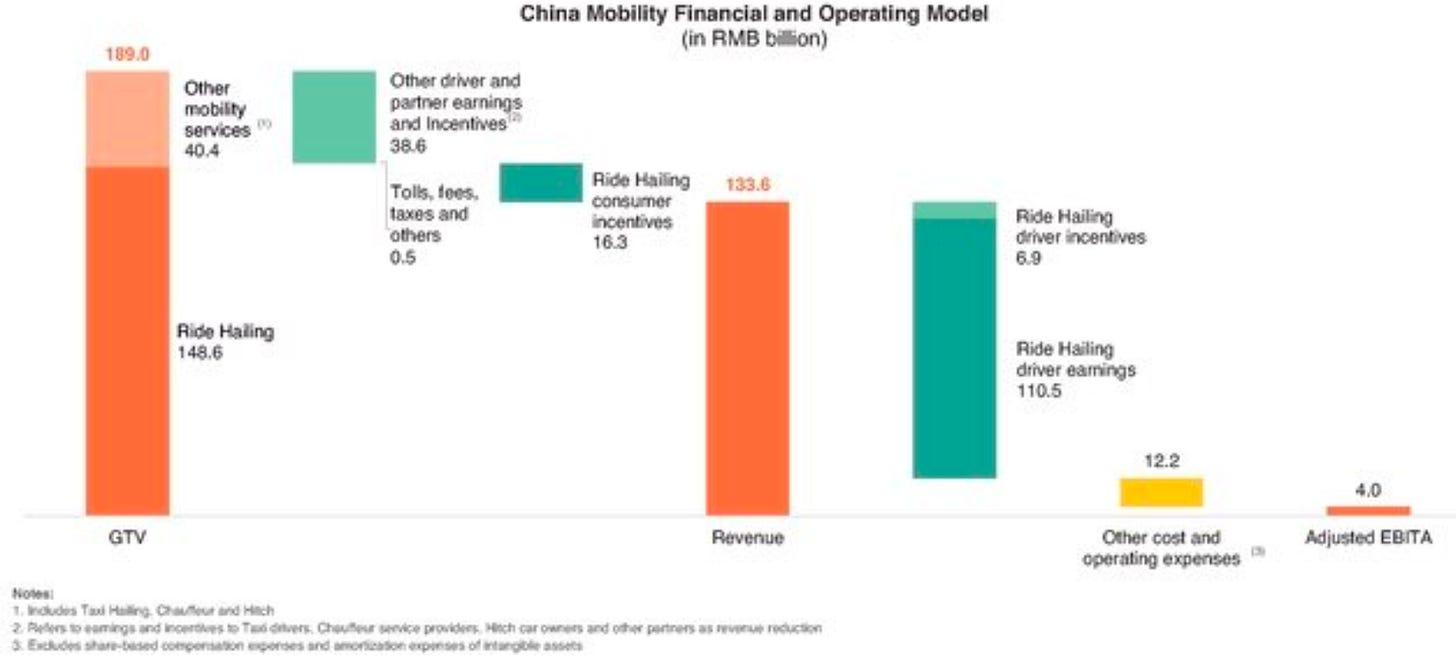

This point is demonstrated by the detailed decomposition of DiDi’s 2020 operating model:

The mixed take rate calculated from aggregated data is dragged down by the low margin of the Taxi Hailing etc business:

My point is that only the take rate of Ride Hailing is comparable to that of Uber. By taking out the taxi-ailing etc contribution, we have an accurate picture of the UE of DiDi’s core business (in 2020). The contribution of taxi-hailing recently is unclear as it was not disclosed, but I expect this part to keep decreasing in the long run.

Margin Expansion

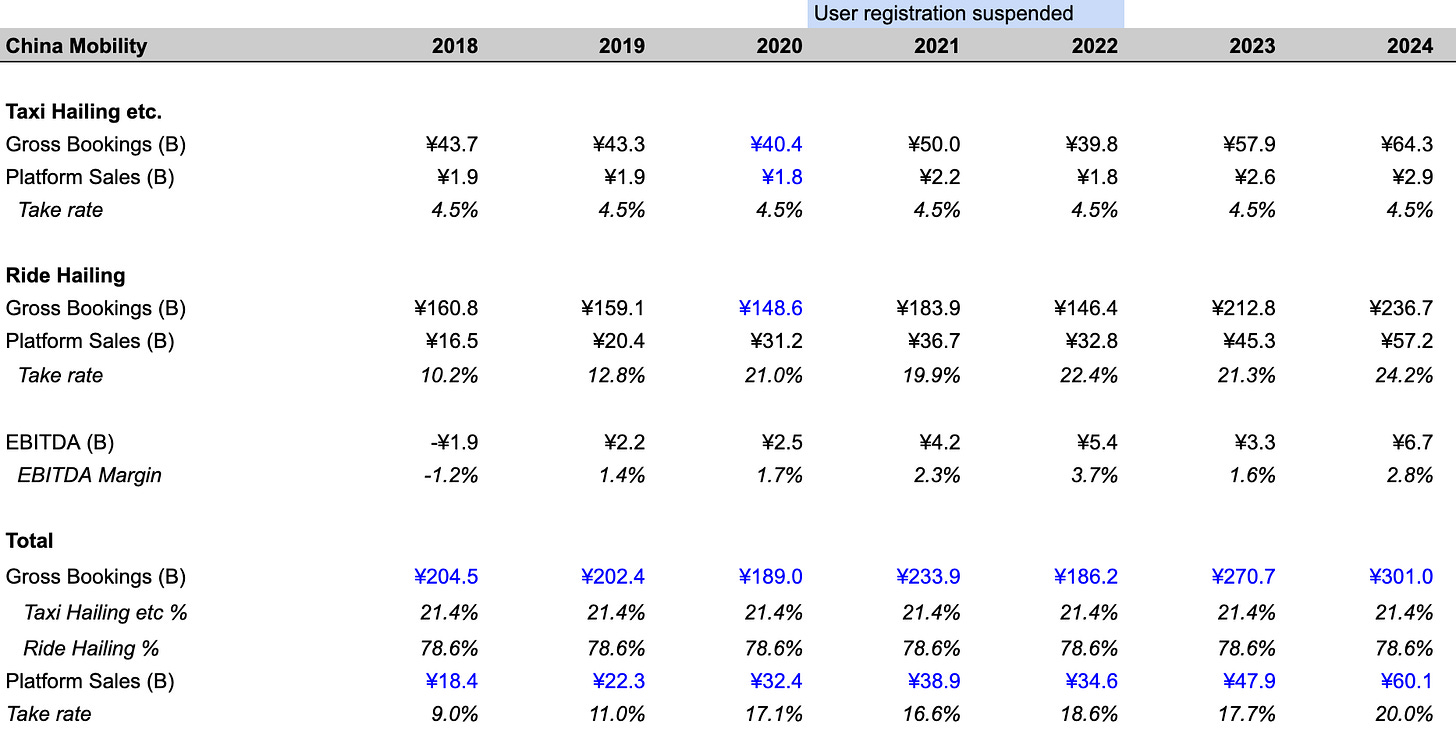

Backing out the contribution from taxi-hailing, by assuming a constant 21.4% GTV contribution and 4.5% gross margin, I estimate the take rate for DiDi’s ride hailing is 24% in 2024.

Can DiDi in China eventually reach Uber’s 30% take rate? It won’t be easy—raising the take rate risks pushback from drivers, especially given DiDi’s dominant market position and the associated antitrust concerns. It is underway though — DiDi has recently introduced various reward cards (such as income boosters and commission waivers), which effectively reduce driver incentives.

Uber’s Mobility segment achieved an 8% EBITDA margin in 2024. For DiDi, I conservatively assume a 6% margin by 2029, factoring in the lower-margin taxi-hailing segment. Given DiDi’s competitive position and an expected more rational competitive environment, I believe a 300-basis-point margin expansion is achievable. For instance, this could come from a 1% increase in take rate, a 1% reduction in consumer incentives (which accounted for 11% of GTV in 2020 per the prospectus), and 1% improvement from operating leverage.

I'll close this section with a question: Given that DiDi's China operations generate roughly the same number of rides as Uber’s global business, should DiDi enjoy greater economies of scale and ultimately achieve a higher EBITDA margin than Uber?

China Mobility IV: 2025 - 2029 EBITDA Bridge

Summarizing previous three sections, for DiDi’s China segment, my model assumes 1) CAGR of GTV is 3%, 8% and 13% from 2025 to 2029 for my bear, base and bull case respectively, and 2) EBITDA margin expands to 6% in 2029 (with simple linear extrapolation).

Combine these together gives 2025-2029 EBITDA bridge. Below is an example for the base case:

International Business

DiDi entered the Latin American market in 2018, first establishing operations in Mexico through the city of Toluca and quickly expanding into major urban centers like Mexico City. Later that same year, it entered Brazil by acquiring the local ride-hailing platform 99 (formerly 99Taxis) for around $1 billion, marking one of its most aggressive international moves.

In both countries, DiDi rapidly grow its user base with its successful local strategy and execution. In Mexico, DiDi reportedly outpaced Uber in trip volume by 2021 in key cities outside of the capital, and in Brazil, 99 maintained strong traction, particularly in tier-2 and tier-3 cities. Since 2018, DiDi’s GTV has grown by more than 10x and shows consistent improving margin profile, suggesting a profit inflection point is around the corner.

DiDi’s Success Recipe for Latin America

DiDi’s success in Latin America stems from its strong local integration and responsiveness to regional issues.19 It formed partnerships with governments, NGOs, and security firms to tackle challenges like public safety and gender-based violence. In countries like Peru, Argentina, and Mexico, DiDi implemented tools such as safety partnerships and data portals for law enforcement. It also invested in community programs, supporting women and education, which helped build trust and strengthen its brand locally.

Additionally, DiDi strengthened its position in Latin America by offering social and financial support tailored to local needs. During the COVID-19 pandemic, it launched a $10 million global fund to support infected drivers and provided disinfection stipends and free rides for healthcare workers.

Beyond crisis response, DiDi introduced financial services like debit cards, microloans, and a no-fee credit card in Mexico and Brazil. Programs like Club DiDi offer discounts, insurance, and financing options, helping build a full-service ecosystem that deepens driver loyalty and sets DiDi apart from competitors. DiDi's financial services segment grew rapidly, with interest income growing by 140% and 79% yoy in 2023 and 2024, respectively.20

High Growth Momentum Ahead

I’m optimistic about DiDi’s future growth in Latin America for two main reasons.

On one hand, Latin America is an ideal market for ride-sharing economy. The total regional population in Latin America has surpassed 660 million, 82% of which will be living in cities. However, public transportation is often unreliable or insufficient, and many cities struggle with traffic congestion—creating natural demand for convenient alternatives like ride-hailing. At the same time, rising smartphone penetration and a flexible labor force make it easier for ride-sharing platforms to attract drivers and couriers.

I estimate that Uber mobility segment has around 30M MAU in Brazil and Mexico combined, implying total penetration rate of ride-sharing in LatinAm is no more than 5%-6%, leaving substantial headroom for growth.

On the other hand, DiDi’s opportunity in Latin America goes beyond mobility. Unlike in China, where sectors like food delivery and financial services are already dominated by giants like Meituan and Alipay, Latin America remains relatively open. DiDi can borrow successful experience from its competitors in China to build a multi-vertical business in the region.

Due to the large under-penetrated addressable market and DiDi’s promising multi-vertical strategy, I assume GTV growth continue its high momentum (30% yoy last year) and gradually slow down to 15% in 2029 in my model. This implies a ¥250B GTV in 2029.

Competitive Landscape and Road to Profitability

There is lack of official data on the market share of DiDi and its competitors in Latin countries. According to what I find from free resources scattered around, my estimate is that DiDi and Uber evenly split the Mexican market, while DiDi (99) holds around 30-40% market share in Brazil.21

I believe that in the end, the local players will either be acquired or merged with DiDi or Uber, as they simply don’t have the resources to compete with global giants.22 Eventually, DiDi and Uber will reach a truce and raise prices together—a win-win outcome. The Uber–Lyft dynamic in the U.S. serves as a clear guidepost: this is the only viable path forward. Let alone it makes little sense for Uber to try to hurt DiDi when it still holds a 10% stake in the company. The timing of this rational equilibrium is uncertain, but it seems to be near the horizon given DiDi’s consistently improving margin profile.

DiDi’s blended take rate (ride-hailing, food delivery and financial service) is 12% in 2024, compared to 24.7% of Uber, suggesting there is large headroom for margin expansion in the long run. However, I think Grab is a better reference in the near-term. Not only Grab just turned profitable in 2023, which I expect to happen very soon for DiDi, Southeast Asia market also shares several structural similarities with LatinAm. In 2024, Grab’s take rate and EBITDA margin is 15% and 4%, respectively.

In my bull case, DiDi achieves profitability in 2026 and reach EBITDA margin 4% in 2029. If the competition is more intensive than expected, EBITDA margin is 3% and 2% respectively for my base and bear case.

2015 - 2019 EBITDA Bridge

In summary, my model assumes 1) GTV growth of DiDi’s international business keeps high momentum and slows down to 15% in 2029, and 2) it turns profitable in next 2 - 3 years and achieve EBITDA margin various from 2% - 4%. Below is the base case 2025-2029 EBITDA bridge:

Other Initiatives ~ Bike Sharing

DiDi’s Other Initiative segment has been where DiDi tucks its wasteful projects. Following the sale of its smart auto business to Xpeng in 2023, there are three business left: Robotaxi (Voyager), intra-city freight (City Puzzel) and bike sharing (Soda).

Robotaxi & intra-city freight

I lump these two together because I believe both business are not very important to my thesis and are unlikely become profitable in the near future.

The robotaxi business focuses on autonomous driving R&D. Like Uber, DiDi’s strategy is to collaborate with car manufacturers. I believe this business is worth maintaining — even if DiDi doesn’t lead the next major breakthrough, staying close to the frontier keeps it well-positioned for future disruption.

As for intra-city freight, it seems like a natural extension of DiDi’s core business. However, I don’t expect it to be easy. Lalamove already holds around 50% market share, while DiDi has just ~5%. And that’s not even accounting for future competition from Full Truck Alliance.

Bike-sharing

Today, 95% of China’s bike-sharing market is dominated by three players: Hello, Meituan, and DiDi, with DiDi holding roughly one-third of the market according to various reports. There is limited publicly available data on this segment, as both Meituan and DiDi do not report bike-sharing results separately, and Hello has remained private since withdrawing its planned IPO in 2021.

Although none of the major bike-sharing players appear to be profitable yet, there are signs that the industry may be approaching a balance, with all three players now incentivized to prioritize profitability through coordinated price increases:

All three major players reportedly raised prices in several Chinese cities in 2024. Prices have increased from the original rate of mostly ¥0.25~¥0.5 per 30 minutes to the current rate of ¥1.5 to ¥1.8 per 10 minutes.23

Bike-sharing is seeing increasing user adoption. According to the Beijing Municipal Commission of Transport, in the second half of 2023, the total number of bike-sharing rides in the city reached 603 million, with an average of 3.3 million rides per day—an increase of 9.9% year over year. The average daily turnover rate of the bikes was 3.56 times.24

In March, YongAnHang, a smaller player in the bike-sharing market, announced that its original shareholder plans to transfer their shares to that of Hello Group. This is seen as the first step for Hello to list in domestic market via reverse merger.25

These developments suggest that (EBITDA) profitability of DiDi’s ride sharing may be within reach in the near future. However, it’s important to consider the capex of this segment, accounting for roughly 75% of the company’s total capex. Unlike ride-hailing, bike sharing is capital-intensive, as DiDi owns and operates the bikes itself.

According to a report I find, DiDi operates 6M - 7M bikes and each bike costs ¥700 -¥1000.26 With a lifespan of 2-4 years,27 I estimate DiDi’s annual maintain capex to be around ¥2B — roughly in line with DiDi’s reported additions to PP&E (bikes and batteries) in 202428.

Cash-burning assumption

Putting things together, I conservatively assume DiDi’s Other Initiatives segment has EBITDA loss no more ¥1B annually over the next five years. With ¥2B capex for bike-sharing, I assume DiDi’s Other Initiatives burns about ¥3 billion in cash per year.

Valuation of DiDi Global

Exit Multiples

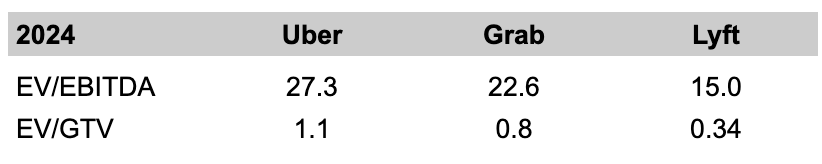

With projected 2025 - 2029 EBITDA bridges from previous sections, exit multiples are the last elements to complete my valuation of DiDi. My main reference is the EV/EBITDA and EV/GTV multiples calculated from DiDi’s peers.

I believe a reasonable EV/EBITDA multiple for DiDi’s domestic and international segments should meet two criteria:

Lyft’s 15x should serve as a lower bound, as it has lower market share and operates solely in mobility, similar to DiDi’s domestic segment.

DiDi’s international business deserves a higher multiple than its domestic segment, as it will remain in an relatively earlier stage with greater growth potential.

Based on this, I assign a 15x exit EV/EBITDA multiple to the domestic segment and 20x to the international segment. As a sanity check, these assumptions imply an EV/GTV of less than 0.9 across both segments and all scenarios.

Sum-of-the-Parts Valuation

Applying the multiples and adding the estimated net cash accumulated over next five years, my model values DiDi Global at ¥500B to ¥812B. This implies a MoM of 3.5x to 5.8x over the five years.

Closing Remarks

In summary, I believe going long DiDi at current levels offers an attractive risk-reward profile. The competitive strength of its domestic ride-hailing business is under appreciated by the market. Combined with its OTC status, the stock is trading at an excessively depressed valuation—effectively giving away its fast-growing international business, bike-sharing operations, and a 3% stake in Grab for free. Based on my segment-level cash flow projections, I estimate a target price range of $14 to $24, implying an IRR of 30% to 43% through 2029.

A few words on DiDi’s founder and CEO, Cheng Wei. An interview conducted by Xiaobo Wu is a great source to get some insight into his character.29 My impression is that Cheng lacks the strong personality or charismatic leadership seen in people like Jack Ma or Richard Liu, suggesting limited independent thinking.

This can be seen by DiDi’s strategic decisions at nearly every stage closely mirror those of Uber. Even the personal anecdote shared in the Founder’s Letter is very similar to that of Uber’s founders.

I still remember that wintery night in Beijing in 2012. It was snowing hard. My jacket was no match for the wind. I wasn't alone. There was along line of freezing people, ahead of and behind me, all waiting with growing frustration for a taxi to take them home. This was a common experience for me since, like most Beijingers, I never had a driver's license. This night was different for me. Unlike the other people in line, I was not frustrated because I had a plan. We launched DiDi that year with the simple goal of making it easier for people to hail a taxi.

— Wei Cheng, DiDi’s Prospectus

However, this background also makes sense to me. Before founding DiDi, Cheng Wei was a manager at Alibaba—a professional manager rather than a grassroots entrepreneur like Jack Ma. From day one, DiDi grew under the heavy influence of capital interests. Cheng’s ability to survive and navigate through this landscape suggests he is skilled at balancing the agendas of various stakeholders. Given the nature of DiDi’s business and the current environment in China, a leader without a strong personality might, in fact, be the best one could hope for.

The author of this write-up owns shares in the companies mentioned and may purchase or sell shares without notice. This write-up represents only the author’s personal opinions and is not a recommendation to buy or sell a security. No information presented in the write-up is designed to be timely and accurate and should be used only for informational purposes. Readers of the write-up should perform their own due diligence before making investment decisions.

I take the preferred shares liabilities at fair value as stated on DiDi’s balance sheet. I think this might be an underestimate of what DiDi needs to pay eventually. However, if I add back the ¥8B fine by the government in 2022, which is a non-operating expense, I believe the underestimation is largely canceled out.

Basically I did a MoM calculation here. Feel free to do a DCF to calculate the intrinsic values with your own assumption of discount rate.

Series article by Len Sherman, professor of CBS: https://len-sherman.medium.com/

Article from Harvard Business Review: https://hbr.org/2019/01/why-some-platforms-thrive-and-others-dont

Research from EqualOcean: https://equalocean.com/analysis/201905021984

Lyft did not disclose their GTV and take rates before 2023. Its take rate grown by 400 basis points in 2024.

See Competition Demystified by Bruce Greenwald and Judd Khan

I think a small portion of market share for its competitors is helpful to maintain a health market and reduce potential antitrust risk for DiDi.

See CaoCao Inc. Prospectus.

There are only 16%-18% riders use both DiDi/99 and Uber in Brazil and Mexico, according to a report from Measureable AI: https://blog.measurable.ai/2022/08/18/ride-hailing-in-latin-america-a-race-between-uber-and-didis-99/

Government expects China’s urbanization rate to reach 70% in the next ten years. This number is 67% today, so the growth can probably be ignored in the near term.

Platform Sale = GTV - Tolls, fees, taxes etc - Drivers’ earnings and incentives

See Note 3.1.21 in 2024 Annual Report.

See Note 3.1.5 of DiDi’s financial statements.

See Note 15 of DiDi’s 2024 financial statements.

I'm really impressed with the details and structure of this article. Thank you a lot for the effort!

Thank you for your article. It is specific and in-depth. In particular, the detailed breakdown of the driving factors is very helpful for modeling. I look forward to your future articles.